The exhibition Folding Concrete is the heart of the SEAM Space in Phnom Penh. Carefully arranged, the individual exhibits open up an exciting dialogue with each other.

More traditionally-minded art lovers might find it hard to believe that such an ambitious exhibition can be found behind the entrance of this house, located in a narrow alley in the Chinese quarter of Phnom Penh. The house itself has seen better times, but the apartment on the fourth floor was recently renovated and made available for the exhibition by a sympathetic art connoisseur who is well disposed towards the curators. The place itself is not a white cube, but a space that curators had to deal with creatively – and it fits perfectly. However, the choice of this location is also due to the fact that Phnom Penh does not have many available spaces for art and urban discourse.

Curated by Lyno Vuth and Sereypagna Pen, the exhibition presents multiple interwoven narratives of modernism in Cambodia through architecture and urbanism and their social and cultural histories. Building upon a research-driven approach, the contribution embraces Cambodian modernities as expansive knowledge that crosses disciplines and scales; presenting various practices and projects.

For the two curators, Folding Concrete in this case has different meanings: “The title comes from three folds. First, in the 1960s, there were many technological advances that gave architects and engineers more possibilities in design and construction. In Cambodia, one of these was folding concrete. Second, the image of folding concrete represents identities of the modernist movement in Cambodia, which can be seen in public buildings, villas, and monuments built during the Sangkum Reastr Niyum period. Third, the folding form of concrete is not a straight line, but is rather a bending in multiple directions, similar to the modernities in Cambodia. They do not come from one field of discipline, but have developed from a variety of fields such as art, culture, architecture, urbanism, industry, and technology.” Folding Concrete opens up arenas of speculation that re-imagine Cambodian modernities. In order to expand the conversation, the exhibition is complemented by public events and lectures.

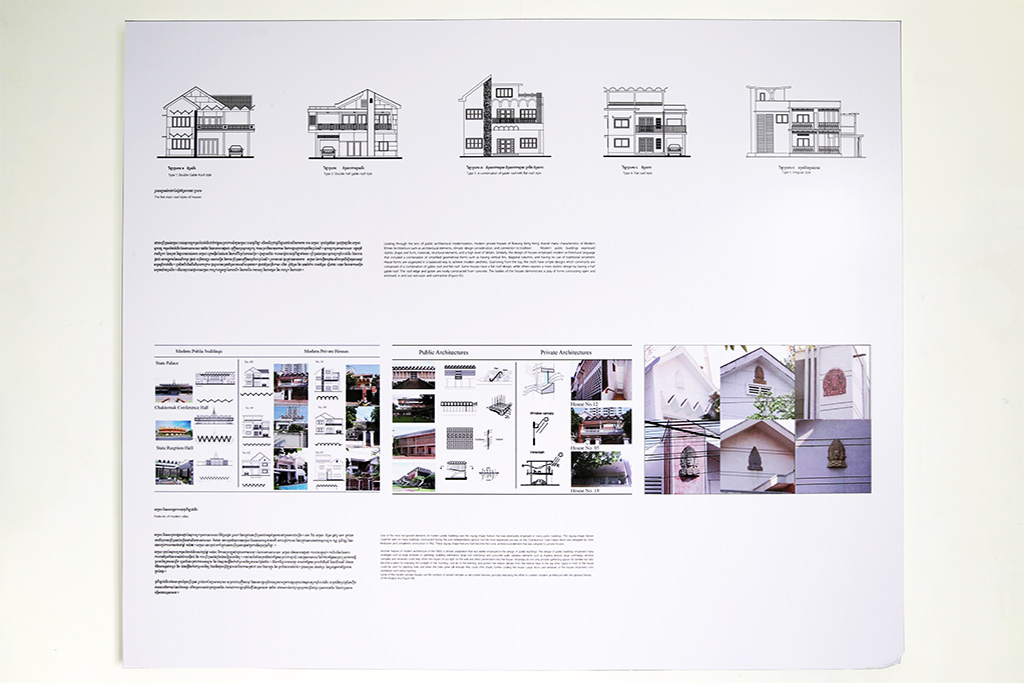

The objects shown cover a wide range of topics, materials, and techniques and are arranged in groups in the rooms of the apartment. The exhibits by Sopheap Pich, Lyno Vuth and Than Sok, Pen Sereypagna, and Chum Panith in the two-storey entrance hall shed light on the iconic White Building that was demolished in 2017. In one of the adjacent rooms, contributions by the Roung Kon Project, Jennifer Austen, and Stéphane Janin address the history of film culture and movie theatres in Phnom Penh through interviews, architectural objects, and photographies. In the third room at the main floor, Measbandol Poum (Bandol) and Sakona Loeung look at typologies and details of New Khmer Architecture, while Dalin Prak’s object merges the structure of a snake (naga) with the territory of Cambodia.

On the upper floor, plans from the Obayashi Corporation Archive document the cooperation between the Cambodian architect Vann Molyvann and Japanese engineers and construction companies. Last but not least, one room is reserved for giving first impressions on the work of the SEAM Spaces in Jakarta, Yangon, and Singapore and another room hosts the Lab.