For Synthesis of Myanmar Modernity, curators Pwint and Win Thant Win Shwin worked closely with documentary filmmaker Kriz Chan Nyein. The Berlin team provided further contributions to this multifaceted exhibition.

After exhibitions on the fifth and sixth floors of a residential and commercial building from the 1960s in Phnom Penh and an “occupied” café in Indonesia’s capital Jakarta, the third chapter of the project was presented at another exciting location: the historic villa of Goethe-Institut Myanmar. The building played a key role in Burmese general Aung San’s fight for independence. From 1945 until the assassination of Aung San in 1947, the house was the headquarters of Burma’s Anti-Fascist People’s Liberation League. The origins of the villa lie in the dark, but it is known that the building was acquired by a wealthy Chinese merchant in the early 1920s, then was abandoned in the turmoil of the Second World War. Later, the State Art Academy was located in the building until 2003. After the resumption of cultural relations between Myanmar and Germany, which had already been established in 1959 but came to a standstill after Ne Win took power in 1962, the villa was completely renovated and expanded by 2018. Today, the house with its garden and café is an invaluable oasis in dense and busy Yangon.

Synthesis of Myanmar Modernity extends on the upper floor of the villa across the foyer and an adjoining classroom. Visitors coming up the open staircase are welcomed by a series of photographs showing Irene, a young Burmese woman in the 1960s and 1970s. The photos have been selected from many hundreds of images from the Myanmar Photo Archive, which was founded by Austrian photographer Lukas Birk. He discovered Irene’s photo albums in a shabby room on the second floor of a typical downtown Yangon building, where they had been dumped by two antique dealers. The images were primarily taken in Mandalay and the surrounding area. It is clearly visible that Irene came from a very privileged background with a car and luxurious house. She was fashionable and was not shy to present her elegance and grace in front of the camera. Irene embodies the 1970s in Myanmar in the way that movies and popular culture imagined it.

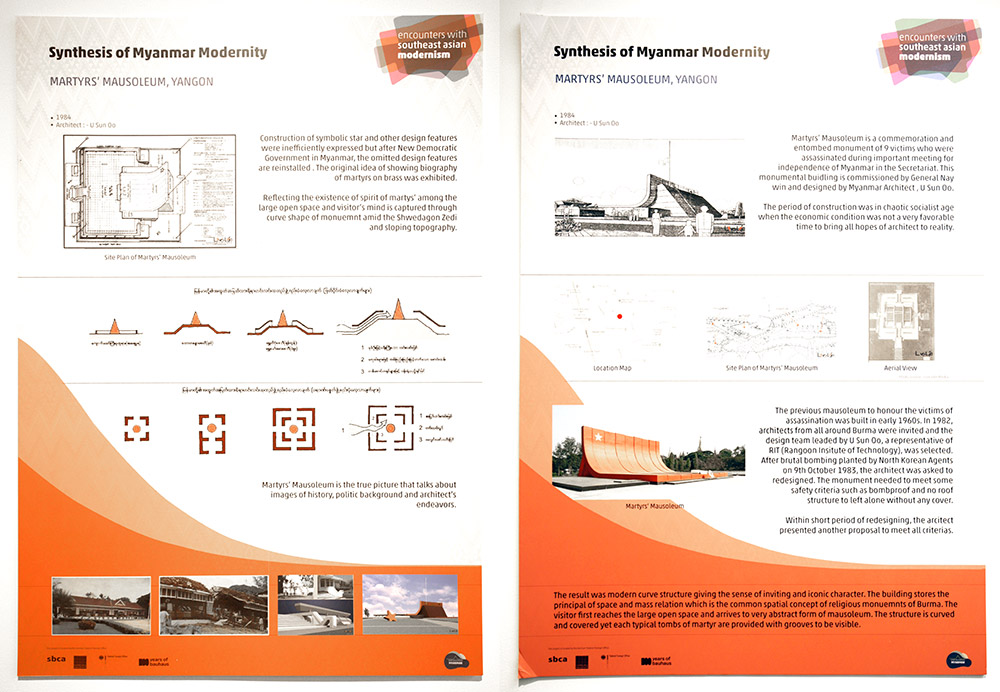

The main part of the exhibition examines three buildings from Yangon’s architectural history after independence: the Pitaka Taik Buddhist Library, completed by Benjamin Polk in 1956, the Martyr’s Monument by architect U Sun Oo from 1982, and the Yangon Regional Parliament from 1974. All three buildings share the attempt to combine design elements of International Modernism with local building traditions, but the results could not be more different.

The Buddhist Library, home to Theravada Buddhist writings, refers with its name to the three pitakas (baskets) of the Pali Canon. However, Burma’s prime minister U Nu did not commission one of the few local architects to plan this important building, but the American Benjamin Polk, co-founder of the Stein Polk Chatterjee Partnership in the mid-1950s, once one of Asia’s largest architectural firms. In 1953, U Nu sent Polk on a trip to the north of the country to learn about the roots of Burmese architecture. Polk designed an impressive building complex, which on the one hand shows clear references to traditional Burmese and Indian architecture as well as to Buddhist mythology, and on the other hand symbolically embodies the dawn of a new era. The ensemble, made of reinforced concrete and intended to last 2,500 (!) years, until the end of the next Buddhist epoch, includes a museum of religious art, a public library, and a lecture hall. The Pitaka Taik Library, completed in 1956 on the northern part of the Kaba Aye Pagoda site, is undoubtedly one of the most important buildings of post-colonial modern Yangon, yet at the same time an example of the interpretation of Burmese traditions by an architect from abroad.

The Martyr’s Mausoleum was built in 1984 to commemorate the nine martyrs, including General Aung San, who were assassinated during a meeting at the Secretariat in 1947 in the run-up to independence. In 1982, architects from all over the country were invited to find a design for the monument. A group of architects around U Sun Oo was selected. However, after a 1983 bomb attack on the building that had been previously located on this site, the team of architects had to quickly revise their design to meet new safety requirements. Nothing remained of their original idea for a stepped, covered pavilion. The result, as the curators describe it, is “a curved, modern structure with an inviting and iconic character. The building embodies the principle of the relationship between mass and space, which is the fundamental principle of Myanmar’s religious monuments.” At the same time, the monumental sculpture also recalls the buildings of Soviet socialism or GDR modernism.

Today’s Yangon Regional Parliament was originally built as a government office, but was rededicated as the local parliamentary seat after the government moved to Nay Pyi Taw. It represents the beginning of the socialist government under General Ne Win. Here, the socialist ideology that dominated the country for many years was developed. Four teams of architects were invited to submit proposals for the parliament building, and U Mg Mg Gyi and his group were ultimately awarded the commission. The shape of the building ensemble, completed in 1974, refers to the country’s traditional architecture, particularly the step-shaped forms found in Myanmar’s famous temple city of Bagan, and combines it with functional modern architecture.

Original drawings and blueprints by the architects U Shwe and U Sun Oo prove the attempts to merge international tendencies with local spatial concepts and building forms. Not only are there echoes of European modernism, but also of postmodern and Japanese and Burmese designs.

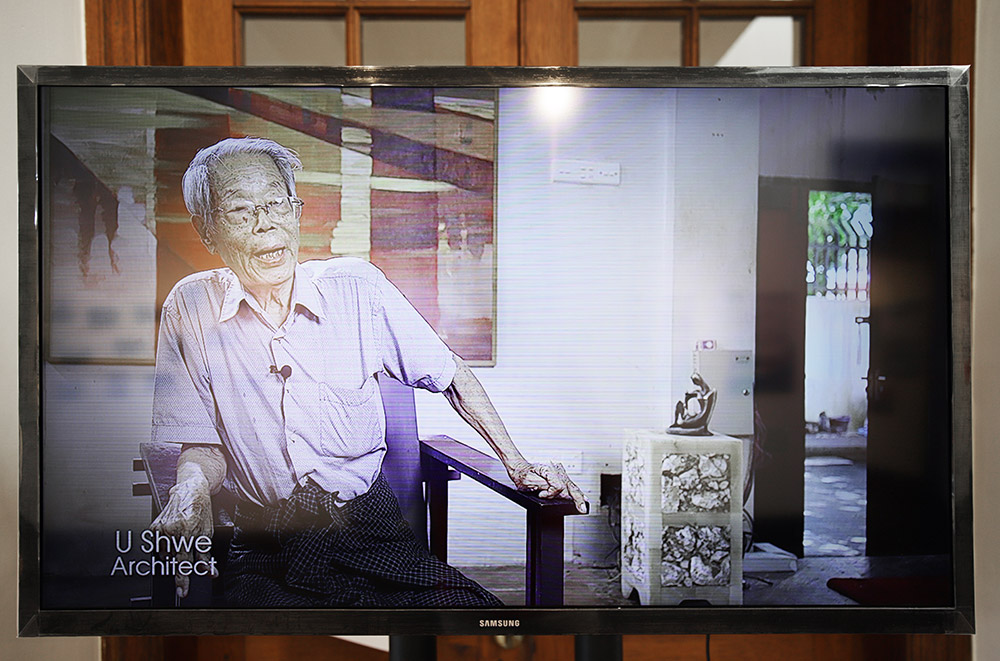

In addition, the exhibition shows excerpts from interviews with architects and artists, which were conducted by documentary filmmaker Kriz Chan Nyein and the curators. The conversations with U Shwe, U Sun Oo, U Win Phae, U Maw Lin and Nay Myo Say focus on the reception of modernism in Yangon from an architectural and artistic point of view. It becomes clear that even in the times when Burma was isolated, a comprehensive examination of Western modernism has taken place. The architect U Shwe traces connections to the work of the Bauhaus, and in particular Walter Gropius, whose work for him stands almost symbolically for the innovative power of modernity. The filmmaker, painter, and radio journalist U Win Phae recalls, “I had a lot of architect friends in the 1960s. They were crazy about the Bauhaus!” The other artists and architects interviewed also repeatedly refer to their confrontation with Western modernism, but also the need to find their own way for the development of the country beyond these inspirations. U Shwe, who studied in Japan starting in 1958, calls this process of influencing in dialogue “cross-fertilization”. For him, it was never a one-way process, but always a flow of ideas in both directions.

Furthermore, a poster designed by Eduard Kögel, part of the Berlin curator team, shows an unrealized design for the Martyr’s Monument, then called Aung San Mausoleum, which was sketched by the Israeli architect Al Mansfeld in 1962. The mostly forgotten images of the sculptural design provided a considerable topic of conversation at the exhibition opening. The design mirrors the complex history of the country after independence. The project also shows that there were manifold relations, not only with the former Soviet Union, the United States, and Great Britain, but also Israel and other countries. This illustrates the openness and interrelations of the country after independence.

Moritz Henning’s article on Yangon’s modernist history, originally published in the German architecture magazine Bauwelt in summer 2019, supplements the pop-up exhibition with a German-language section and the translation of this seminal text into the Myanmar language.

One of the highlights of the exhibition is a seating group consisting of two armchairs and a side table, designed by the architect U Shwe’s office for a private residence he completed in 1989: “Bauhaus meets Japan, designed by a Burmese architect,” U Shwe commented on the designs of the furniture at one of our meetings.