The introductory text is summarized from a preliminary talk with Tay Kheng Soon. The subsequent interview with him was conducted by Eduard Kögel and Ho Puay-peng on 27 November 2019 in Singapore on the occasion of the SEAM Space Singapore.

Tay Kheng Soon is without question one of the most prominent architects, planners, and critics of Singapore’s urban development. He was one of the first students to witness the emergence of the Singaporean scene in the late 1950s and early 1960s. As a young architect, he designed several buildings that are now icons of the post-independence period after 1965.

Starting in 1959, Tay Kheng Soon studied in the first class at the first school of architecture, the Singapore Polytechnic. The most influential teacher there was Lim Chong Keat, who introduced the preliminary course of the Bauhaus. Lim had studied in Great Britain (Manchester) and in the USA (MIT), where he was exposed to the ideas and ideals of the modern movement. In Singapore, everyone agreed that students should prepare for the future, and no one had any idea what this would look like until the Singapore Conference Hall opposite the school was built by Malayan Architects Co-Partnership (1961–1967, by Lim Chong Keat, Chen Voon Fee, and William S.W. Lim).

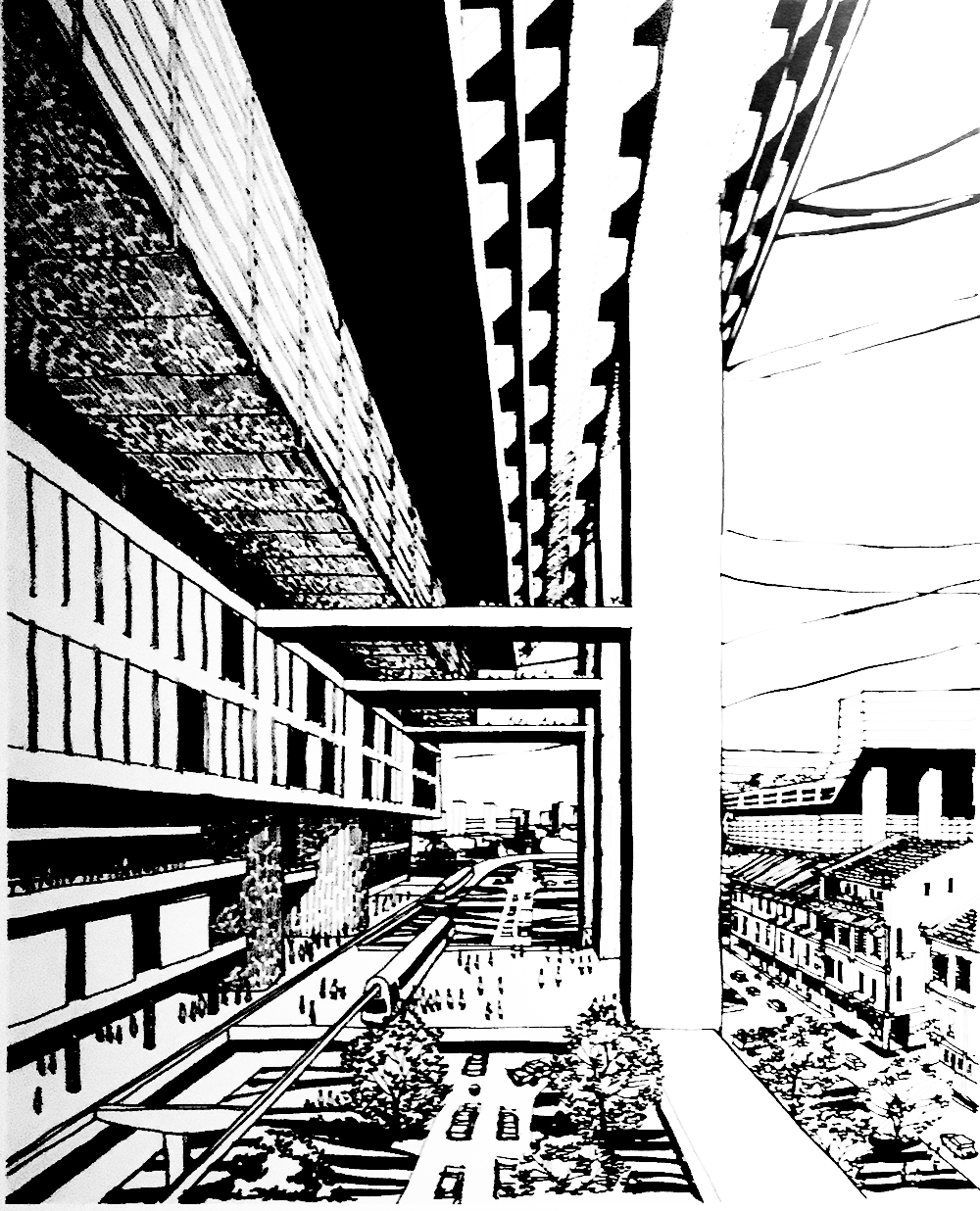

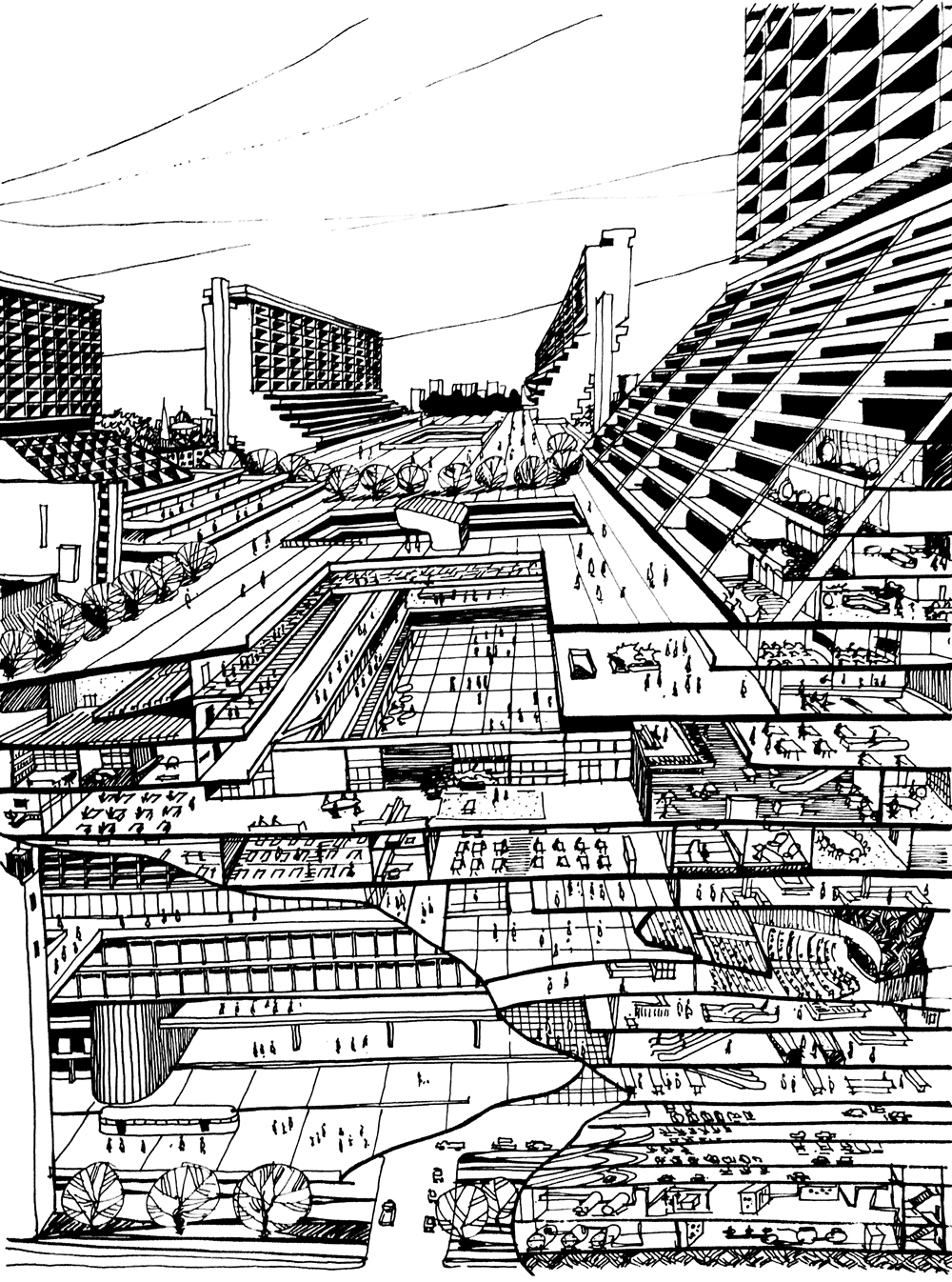

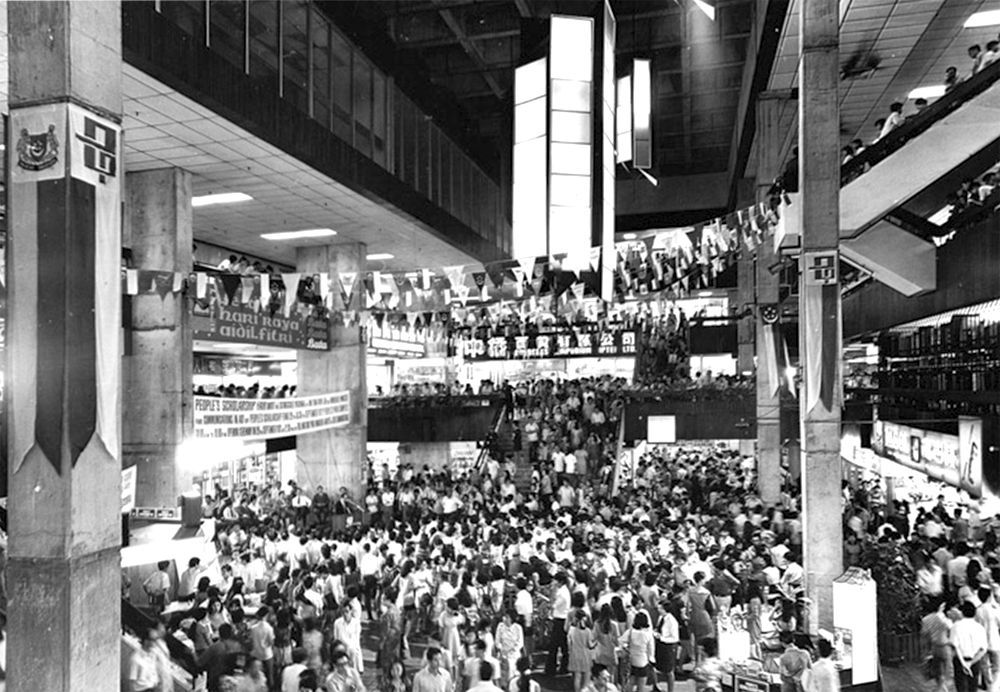

After graduating, Tay worked in the office of Malayan Architects Co-Partnership, where designer Lim Ching Keat set the tone. Later in the 1960s, Tay Kheng Soon travelled around the world, visiting India, Turkey, Japan, Israel, and Greece, among others, where he met Konstantinos A. Doxiades in Athens and learned about his ideas on Ekistics. Lim Chong Keat and William S.W. Lim gave him their contacts in the international architectural scene at the time and even lent him money for the trip. After his return, Tay Kheng Soon and William Lim founded the think tank Singapore Planning & Urban Research Group (SPUR) together with many other experts with different backgrounds. In 1967, Tay Kheng Soon, William Lim, and Koh Seow Chuan founded the architectural firm Design Partnership, where Tay was a partner until 1974, before continuing with his firm Akitek Tenggara. With Design Partnership, Tay realized iconic, multifunctional, brutalist buildings, such as the People’s Park Complex and the Golden Miles Complex, both designed and built between 1967 and 1973 and now threatened with demolition.

Eduard Kögel (EK) How did you start your professional practice?

Tay Kheng Soon (TKS) In the mid-1960s, I was very involved, together with William Lim, in setting up the Singapore Planning & Urban Research Group (SPUR, 1965–1975).

EK This was even before you founded Design Partnership?

TKS That was before. Lim Chong Keat was not happy because he was close to the government, and we criticized the work of the government, the relocation of the population to public housing, standardized housing, and all that. In fact, I organized a public exhibition about Singapore’s environment – past, present, and future. In the exhibition, I showed pictures of Housing Board apartments and chicken coops side by side. This upset the government. We spent a lot of time studying on our own about planning the environment. We spent a year on it, and then we came across the expansion plans for the old Paya Lebar Airport. I announced in the press that it was a disastrous project because it would have sterilized a quarter of the island with its flight paths, and we pushed for the airport to be moved to Changi, where it is now: that upset a lot of people. For me, architecture and planning are closely connected; to separate them is absurd. That is my criticism of architecture today.

EK But that is often the reality today. Yesterday we visited some projects in the city with beautiful design but without any connection to the surroundings.

TKS The buildings must be created out of their context and not be conceived as an isolated sculpture. But that is what most architecture is today, a work of art without meaning.

EK In the case of the People’s Park Complex, it is immediately apparent that this is an urban project. It has a commercial podium that is open to the surrounding area and the residential slab stands above it. Is this the first result of your research approach at SPUR?

TKS Yes, definitely. I think it came through my experience in research and from Tokyo. In Tokyo, I learned that you don’t have to shop on the street level. As long as you have escalators, you can go as high as you want. That was an experience in Shinkenchiku in Tokyo. Another aspect is the kind of geometry that invites people to move, as I have seen in modern architecture in Israel.

EK Did you meet Arieh Sharon there?

TKS I can’t remember their names. The guy I met studied with Willy (William Lim) at the AA in London. Back then, they were all some kind of semi-Marxists. If you weren’t a Marxist, you were branded an idiot.

EK So the concept for the People’s Park Complex arose from your experience during your travels in Japan and Israel?

Ho Puay-Peng (HPP) Why Israel?

TKS I learned the staging of exact geometry in Israel, with which I could get people around corners and up, with overhanging volumes and the like. I wish I had kept some of my early sketches, but I have none of them. I moved several times and threw everything away.

EK But how did the client react to the programming of the building?

TKS He found it very interesting. Willy and I worked out the economics of the project. We went to the client and told him he could make millions. He just answered, tell me how. Just go ahead, I don’t care what you do, as long as I get the money. The design was completely in our hands and we got the full fee, seven-and-a-half per cent – unheard of since. We thought about how many units we could build on each floor and at what price they could be sold.

HPP But you didn’t sell them yourself?

TKS The client sold them, but we organized the whole sales program. We had a big public exhibition with models and even did tours where the shopkeepers from Chinatown came with suitcases full of cash.

HPP This project was very pioneering.

TKS The idea of multiple ownership was completely new. There was no strata title back then. I scheduled a meeting with Mrs. Lee Kuan Yew (Kwa Geog Choo), a top lawyer. I went there with the client and showed the documentation of the project. She immediately saw the problem and said, let me do something about it. The Strata Title Bill came out afterwards. The problem was the apartments up on the podium. How can you distribute the maintenance costs? The value of the apartments on the podium is almost nothing compared to the value of the mall. If the costs are shared, the residents are in a bad position. This had to be clarified. It was a very difficult matter; here too we were pioneers. Through this project we became the go-to architects for shopping centres. We then built three or four shopping centres in Kuala Lumpur and Singapore.

EK Since this is pioneering work in many ways, the building should be preserved, right? It is a witness to the changes that new building typologies bring about in the existing business and social environment.

TKS This is a completely money-driven society without further interests. What does an old run-down building mean here?

EK Years ago, Chinatown was also in a very bad condition. It was easy to tear down because it seemed worthless. Today, nobody can imagine that anymore. When another 20 years have passed, the same will be true of the iconic buildings from the time after independence.

TKS Chinatown is the reason the protection of historic architecture was put in place. The tourism industry first noticed in the 1980s that tourists didn’t come to see the shiny new buildings, but to see the old ones. That is why Chinatown was preserved. So it’s for the money, not for sentiment.

HPP I have another version for you. Many years ago, I was invited to dinner with Lee Kuan Yew in Hong Kong. I asked him why Singapore started this conservation project. He said, I went to Delft and was very impressed with Delft. I asked him why Delft? You have been to many cities in the world.

TKS He also said Singapore is condemned to build and rebuild forever. This is the reality. There is no sentimental reason – only money counts.

EK But maybe there is a reason to build a story about the buildings that is not just commercial value. It could tell about the history.

TKS History is all in the books. Especially his-story.

EK Would you argue that this is a fundamental difference between Europe and Singapore or Asia?

TKS Here, history is very weak.

EK In the case of China, we can observe a growing sensitivity in dealing with historical traces in the urban environment. Even buildings from the 1950s and 1960s are being reassessed. I have the impression that there is a shift towards material history rather than immaterial memories.

HPP Maybe it will come to Singapore, I’m not sure. But certainly not now.

EK Yesterday, the driver of my taxi at the People’s Park Complex pointed to it and said, This is the next one. I said, What? And he said, It’s gonna be destroyed soon, because Singapore thinks it doesn’t need history.

HPP This is because the Pearl Bank apartment building is in the immediate vicinity and is in the news a lot. [The high-rise Pearl Bank Apartment, designed by Tan Cheng Siong in 1976, was demolished at the end of 2019. There was a debate in the press about whether such iconic buildings should simply disappear.]

EK In the case of the People’s Park Complex, one could renovate, as the shopping centre alone has great commercial potential.

TKS The colour of the complex is terrible today. Originally, it was only natural concrete. Someone asked me to suggest some ideas for the renovation. So I proposed to create a Chinese garden on the roof of the shopping centre with imported old wooden buildings from China, which are used as big restaurants. That would be fun, right?

HPP I hope you do that.

EK Do you think there is a real chance to renovate or save the building?

TKS I don’t know. It depends on the ownership situation. The current owners don’t want to change because they do good business. The person in charge is respected like a local authority. But many of the small shop owners want to sell, so it’s a complex case.

EK And what is the situation now at the Golden Miles Complex?

TKS The problem in Singapore is that you cannot transfer your development rights from one place to another. If you want to secure a building and the ratio was originally three, but has meanwhile increased to six, the developer would say, I’ll preserve the building if I can transfer my rights to another side. But here you have a legal problem with that. In Singapore, the legal system favours the government and not the landowner. This is the socialism of the early days. Singapore is legally socialist and operates in a capitalist mood.

HPP Like China today.

TKS It appears that China is learning from us.

EK In China, the role model is Singapore. But to come back: Do you personally want to see buildings like the People’s Park and the Golden Miles Complex preserved?

TKS I am sceptical about it now. Nowadays the spatial design of the city is much more important. The evaluation should not be made on an architectural scale, but on an urban scale. Architecture is only very important for buildings such as museums or religious buildings. But the city is not architecture: the city is a continuous spatial system, that’s all.