As a public prelude to the project Encounters with Southeast Asian Modernism during the Bauhaus centenary, the symposium in Berlin brought together international curators and experts to explore the history and presence of modernism in Southeast Asia in four select cities.

More than 100 guests accepted the invitation to the first public event of the project in Berlin. The afternoon began with a welcoming address by Dr. Stefan Buchwald, Head of the Department for Cultural Relations Southeast Asia, Australia, New Zealand & Oceania at the German Federal Foreign Office, whose support made the project possible. Eduard Kögel moderated the first panel. For the secon panel, Ute Mata Bauer took over the microphone.

Shirley Surya, curator for art and architecture at M+ museum in Hong Kong, was the first speaker. She presented the future collection and exhibition strategy of M+. The new museum was designed by Herzog & de Meuron and the building is scheduled for completion in 2020. M+, located in the West Kowloon Cultural District of Hong Kong, aims to become one of the largest museums for modern and contemporary visual culture in the world and a distinctive and innovative voice for Asia in the 21st century. Its particularly promising approach brings together works from various disciplines into dialogue to illustrate the diversity of this fascinating region, raise new questions about it, and explore its relationship to Hong Kong.

Johannes Widodo, associate professor of architecture and urban history in Singapore, used the example of Sir Banister Fletcher’s A History of Architecture, first published in 1896, to describe the ongoing disregard for architecture from entire regions of the world, such as Southeast Asian architecture. Fletcher’s book, which was used in architectural education for decades, focuses on European architecture from the Romanesque period to the Renaissance, but also mentions the buildings of the British colonies and the USA as “historical styles”. Meanwhile, architecture from India, China, and Japan are identified as “non-historical styles”. This interesting perspective is further illustrated by a genealogical tree which, in the best colonial tradition, dedicates the trunk to the development of European building culture, while allowing the building culture of the rest of the world to die off halfway. Since the beginning of the 2000s, according to Widodo, a number of networks, such as the current mASEANa project led by docomomo, have been devoted to a well-deserved reappraisal of Southeast Asian modernity.

Puay-Peng Ho, professor of architectural history in Singapore, presented the development of housing construction in the Southeast Asian city-state based on the development of the Tiong Bahru Estate. It was interesting to see how, at around the same time in both Singapore and in Berlin, very similar images of poor residents in their dilapidated dwellings were contrasted with the promises of the radiant, white world of modernism.

Win Thant Win Shwin and Professor Pwint from Myanmar addressed the development of modern architecture in their country, which was initially strongly influenced by architects from abroad. Particularly impressive was the insight they gave into the development of architectural education in Myanmar, which reflects the country’s varied history.

Setiadi Sopandi, a curator and architect from Indonesia, raised the interesting point of whether modernist architecture had a relevant influence on society at all: “We question how modernist architectural language, elements, and approaches may have brought about significant contributions to the society – beyond the aesthetic stance and the beautification of Indonesian cities,” he asked the audience. Given the disregard and rapid disappearance of architectural testimonies of this epoch in Southeast Asia, this is an extremely topical question.

Avianti Armand, curator of the SEAM Space Jakarta with Setiadi Sopandi, provided a detailed look into the preparations of the project in the Indonesian capital. Their exhbition Occupying Modernism: Impressions on Indonesian Modern Spaces reflects on how Indonesians have rendered their spaces of modern architecture. Four artists will explore at least four sites: two public spaces and two domestic environments. The artists are asked to visit, observe, comprehend, and establish a certain perspective or develop an idea that will potentially enrich our understanding of the modern spaces. Through the creative and imaginative impressions by the artists, the exhibition will address how Indonesians have occupied – celebrated, used, loved, cared for, disturbed, damaged, left behind, hated, ignored, and rediscovered – our modern spaces.

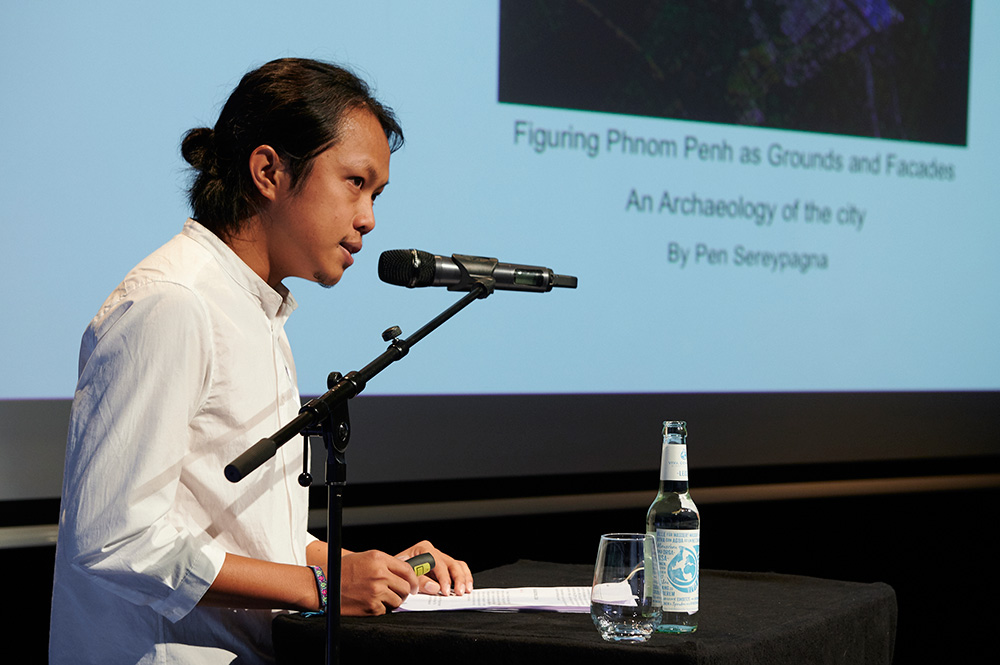

Meanwhile, Sereypagna Pen, one of the two curators from the Cambodian capital city of Phnom Penh, took the audience on an archaeological journey through the history of Phnom Penh from its foundation until the present.

Artist and curator Lyno Vuth examined the struggle over the modernist discourse and its promises in Cambodia, based on an analysis of several exhibitions held in Phnom Penh between 1955 and 1967 which championed the advantages and achievements of the modern world.

The last lecture of the evening was reserved for farid rakun of the artist collective ruangrupa. In his lively presentation with fascinating video footage, he described the development and professionalization of the ruangrupa collective, which will curate documenta in Kassel in 2022.

In the final discussion, with Shirley Surya, farid rakun, Lyno Vuth, Puay-peng Ho, and Pwint moderated by Ute Meta Bauer from CCA in Singapore and Eduard Kögel on behalf of the project organizers, questions on education and training came into focus. What kinds of concepts should be developed – by museums such as M+, alternative educational sites such as Gudskul by ruangrupa, or universities – so that students and the general public can be introduced to socially relevant issues?

The day closed with a reception in the TAK courtyard. As became clear in the subsequent conversations, many guests had been little aware of how complex and multifaceted the discussion on modernism in Southeast Asia actually is. Of particular interest to the public was how the modernist discourse is being approached from a less Eurocentric perspective, which was also reflected in some of the lectures.

What quickly became clear was that the history, significance, and future of “messy modernism” – as Johannes Widodo described the perception of Southeast Asian modernism with reference to the many unresolved questions – still leaves much more to explore. We hope to contribute to the discussion with the four upcoming events in Phnom Penh, Jakarta, Yangon, and Singapore.